THERE IS TREMENDOUS value to facing things head-on; to rooting yourself firmly and unshakably in reality, unmoved by the maelstrom it periodically unleashes. Hic et nunc, as the Stoics put it. To be immersed in the here and now. But some days, the going can get too tough, the waters too choppy. These are the days when staying afloat feels next to impossible.

During these moments, it helps to have a hobby or ten to buoy the spirits. These hobbies act as temporary escape hatches—a place where the mind can rest as the soul regroups. As someone who’s been struggling with cycles of anxiety and depression, I understand the value of escapism. I’ve always gravitated towards solitary (and sedentary) activities like writing, reading, singing, playing the guitar, crocheting, and cross-stitching. All these hobbies help shift my focus away from what’s stressing me out at a particular moment.

Out of all these activities, there’s one that I’ve turned into a daily habit, and that’s reading. Reading a few pages at the end of a long day can help cleanse the mental palate. Bonus points if the book teaches you something. Though, to be fair, all books have something to teach—even if the lesson is something as left field as when to quit reading a bad book.

Normally, I rely on book lists and recommendations to find out what I ought to read next. This year, however, I’ve had to nix my prepared list. Health problems. I have an autoimmune disease that leaves me with brain fog and fatigue. And because focus and energy are two things I have in low supply at the moment, I need to be very selective with my readings. Nothing too long or too demanding. So, expect most of the books on this list to be on the short (but superb) side.

Alors, without further ado, my first ten books for 2021:

Book 1: The Night Diary (2018) by Veera Hiranandani

Favorite Quote: “Papa says that everyone is killing one another now, Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs. Everyone is to blame. He says that when you separate people into groups, they start to believe that one group is better than another. I think about Papa’s medical books and how we all have the same blood, and organs, and bones inside us, no matter what religion we’re supposed to be.” – Veera Hiranandani, The Night Diary

Set in 1947, at the height of the Indian Partition riots, Veera Hiranandani’s The Night Diary follows the story of one family as they escape religious persecution in their homeland. The story unfolds as the diary entries of 12-year-old Nisha. She uses her diary to write to her mother who had passed on when Nisha and her twin brother, Amil, were babies.

Now, the fact that we’re reading about the Partition—one of the bloodiest and most devastating episodes in Indian and Pakistan history—through the experiences of a 12-year-old girl makes everything even more painful. Her family’s journey from Pakistan to the New India is perilous and heartbreaking. At one point, Nisha is held at knifepoint by a man whose lost his entire family during the riots.

Though the book is a quick read, it is not a light one. The Night Diary is a complex and moving book that explores challenging and important themes like family problems, religion (and the role that it plays in our perception of others), social class, social/racial/religious identity, justice, and finding one’s voice.

A must-read.

Grade: A-

Book 2: The House on Mango Street (1984) by Sandra Cisneros

Favorite Quote: “One day I will pack my bags of books and paper. One day I will say goodbye to Mango. I am too strong for her to keep me here forever. One day I will go away.

Friends and neighbors will say, what happened to that Esperanza? Where did she go with all those books and paper? Why did she march so far away?

They will not know I have gone away to come back. For the ones I left behind. For the ones who cannot get out.”

The House on Mango Street is a series of vignettes told through the perspective of its heroine, Esperanza Cordero. Each chapter offers a slice of Esperanza’s life. It gives the reader an idea of what it must be like to be a 12-year-old Chicana growing up in an impoverished Hispanic neighborhood in Chicago.

Fair warning, this is a book that tackles sensitive topics like racism, sexual harassment, and domestic violence. It may be a slim volume but you can be sure that it packs a proverbial punch. It’s definitely the type of book that stays with you long after you’ve turned the final page.

Another thing I love about the book is how authentic it reads. I can practically hear Esperanza’s voice in my ear. It’s so well-written, the lingo is spot-on, and it’s emotionally honest without the histrionics. What else is there to say? Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street is definitely worthy of a spot on your reading list.

Grade: A

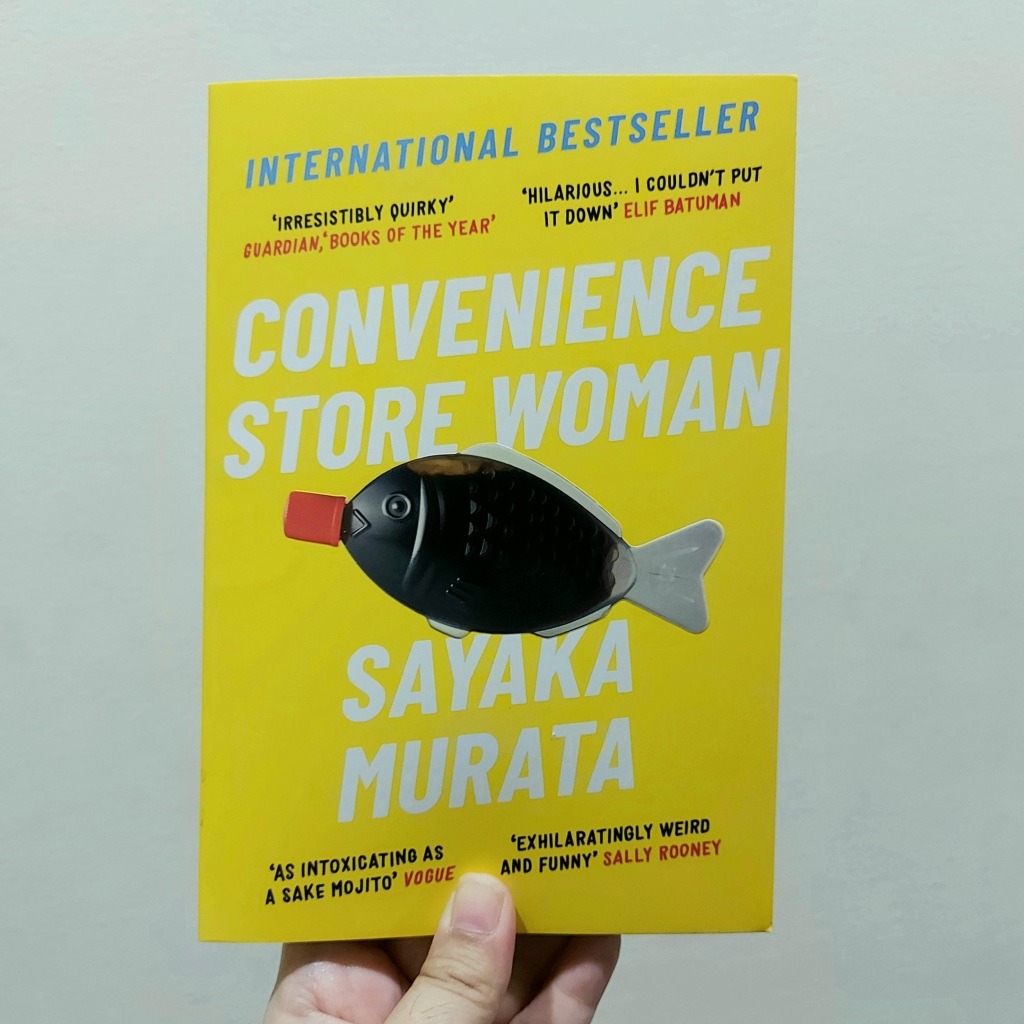

Book 3: Convenience Store Woman (2016) by Sayaka Murata (possible spoiler ahead)

Favorite Quote: “The normal world has no room for exceptions and always quietly eliminates foreign objects. Anyone who is lacking is disposed of.

So that’s why I need to be cured. Unless I’m cured, normal people will expurgate me.”

Convenience Store Woman is the heartwarming story of the awkward and endearing 36-year-old Keiko Furukura. As the book’s title suggests, Keiko is a proud Smile Mart employee in the Hiromachi neighborhood in Shinagawa. She’s had the same job for over 18 years, and it’s a job that she’s absolutely passionate about. To Keiko, it’s more than work—it’s her life. Working in a convenience store brings direction, stability, and purpose to her existence. It’s also where she takes her cues on how to live like a “normal” person. Now, if only society and the people around her would stop trying to mold her into something she’s not.

Out of the ten books in this list, this is my second favorite. The premise is quite simple. Quirky/misunderstood/boring middle-aged protagonist faces crushing societal pressures. Square peg forced into round hole shatters the mold—that kind of book.

Now, the plotline isn’t wholly new, but maybe that is its genius. Keiko’s struggles are universal. It’s the question of whether one should conform to society’s expectations and reap the benefits that come with that ‘peaceful’ existence or stay true to oneself and risk becoming an outcast. I think that while our experiences may differ, this is a dilemma we’ve all faced at one point or another. It’s a simple, sweet, funny, and heartfelt book. A perfect read all year round.

Grade: A+

“I am one of those cogs, going round and round. I have become a functioning part of the world, rotating in the time of day called morning.” – Sayaka Murata

Book 4: Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) by Jean Rhys

Favorite Quote: “There are always two deaths, the real one and the one people know about.”

Philip K. Dick once said, “It is sometimes an appropriate response to reality to go insane.” Now, if you’ve ever wondered about the madwoman in Jane Eyre’s attic, then this book is the salve for that particular itch. In Wide Sargasso Sea, author Jean Rhys breathes life—and what a fascinating and tragic life it turned out to be—to the infamous and violently insane, Bertha Mason. Of course, she wasn’t Bertha then. She was the beautiful, proud, and vulnerable Creole heiress, Antoinette Cosway.

Antoinette’s early life can only be described as wretched. Her family loses all their money, her mother goes insane, her brother dies early, and she’s left with no one to really love her or care for her. If not for her stepfather’s sense of responsibility, our heroine would’ve been out in the streets, or worse, dead. But the arrival of a certain Mr. Rochester might just change everything.

Of course, he marries her for her dowry, which is hardly ever a good thing, but he also presents her with the possibility of happiness and a fresh start. So where did it all go wrong? Why did our heroine go mad? Was Antoinette’s madness genetic or was it the consequence of neglect and a hostile environment? The book answers all these questions while also delving into postcolonial issues of sexism, racism, prejudice, cultural clashes, assimilation, and displacement.

Wide Sargasso Sea is undoubtedly a very important piece of literature. It’s a solid read and one that I do recommend to people who love classics. But, personally, I wish the writing and the plot were a little tighter or cleaner. I don’t know how else to describe it other than reading the book is like walking into someone’s dream or nightmare. The scenes are very vivid, but the pace is unpredictable and there are gaps in the story and the timeline that I wish were a little more fleshed out.

Grade: B

Book 5: The Duke and I (2000) by Julia Quinn

Favorite Quote: “A duel, a duel, a duel. Is there anything more exciting, more romantic…or more utterly moronic?”

A few years ago, two dear friends introduced me to the exciting world of Historical Romance. Their recommended starters? The whole Julia Quinn catalogue, starting with the first book in the Bridgerton series, The Duke and I. Now, I wasn’t planning on rereading the series just yet, but Netflix has inspired me to revisit Quinn’s works. And I’m sure glad I did.

Set in Regency London, The Duke and I is the story of how the commitment-averse Simon Basset, Duke of Hastings, and the lovely and quick-witted Daphne Bridgerton set out to dupe the ton into thinking they’re in love. Simon is determined never to marry and by pretending to court Daphne, he has a built-in excuse to keep the marriage-minded society mommas at bay. As for Daphne, she’s hoping their little plan can make her more desirable in other men’s eyes. After all, a Duke did choose her, right?

Naturally, their plan backfires. Love gets in the way. As far as hisrom books go, this has all the elements for a good one. You have the couple getting caught in a compromising position, a duel, family drama, and a dark secret that threatens to destroy all semblance of happiness for Simon and Daphne. It’s a great, quick and fun read. I highly recommend it.

Grade: B+

Book 6: The Viscount Who Loved Me (2000) by Julia Quinn

Favorite Quote: “A man with charm is an entertaining thing, and a man with looks is, of course, a sight to behold, but a man with honor—ah, he is the one, dear reader, to which young ladies should flock.”

The Viscount Who Loved Me is the second book in Julia Quinn’s Bridgerton Series. This time, the book centers on the eldest of the Bridgerton siblings, Anthony. With his best friend, the Duke of Hastings, off the market (and married to his little sister, no less!), Anthony has become London’s most eligible bachelor. Except he’s not looking for a bride, he’s already chosen one.

Edwina Sheffield is smart, beautiful, amiable, and someone Anthony’s sure he will never fall in love with. In short, she’s the Viscount’s idea of the perfect bride. It’s just a matter of wooing her and getting the approval of her stubborn, willful, infuriating, and utterly irresistible older sister, Kate. Somehow, when Kate’s around, Anthony just can’t seem to bee-have. Yes, I did that.

The Viscount Who Loved Me is a strong second offering from the Bridgerton Series. I found it to be more lighthearted, generally a quicker and easier read than The Duke and I. At times laugh-out-loud funny, at times secondhand cringe-inducing, this is a book that has enough ups and downs to keep you on the edge of your seat.

Grade: A-

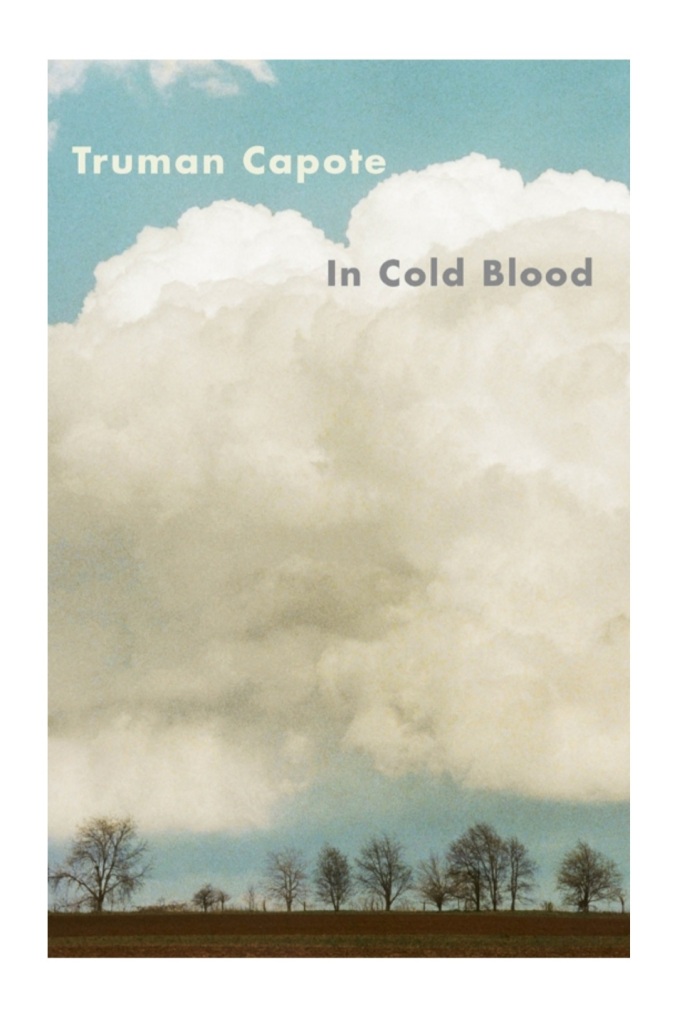

Book 7: In Cold Blood (1966) by Truman Capote

Favorite Quotes: “The village of Holcomb stands on the high wheat plains of western Kansas, a lonesome area that other Kansans call ‘out there.’”

“Just remember: If one bird carried very grain of sand, grain by grain, across the ocean, by the time he got them all on the other side, that would only be the beginning of eternity.”

“I thought that Mr. Clutter was a very nice gentleman. I thought so right up to the moment that I cut his throat.”

And now, my favorite book in this list—In Cold Blood by Truman Capote. The book covers the Clutter family murders and the arrest, trial, and execution of murderers Richard “Dick” Hickock and Perry Smith. As a true crime fan (the genre, not the activity), I don’t know why I waited so long before reading this seminal piece.

This is a book that shaped an entire literary genre. The fact that it’s still the second-best-selling true crime book over 50 years since its publication shows us how important and impressive In Cold Blood is. Now, I know the book has veracity issues, but I won’t be touching on that. For now, I’m basing this mini-review on my experience as a reader. And all I can say is that In Cold Blood is exquisitely written and worth the many praises it’s received from readers and critics alike.

All the characters—the Clutter family, Dick, Perry—are so fleshed-out that you can picture them as they were before their lives took a very tragic turn. It was a senseless and brutal murder that left an entire nation reeling and a town devastated. The murderers were completely inhuman in their cruelty, and yet Capote manages to somehow humanize these killers—especially Perry Smith. By doing so, the author makes the crime all the more terrifying and disturbing.

This is a staggering book. If you love good writing, true crime, and the classics, this is one for your shelf.

Grade: A+

Book 8: The Giver (1993) by Lois Lowry

Favorite Quote: “The life where nothing was ever unexpected. Or inconvenient. Or unusual. The life without color, pain or past.”

Here’s a book from my childhood—and maybe yours as well. The Giver is a dystopian tale that follows the story of 12-year-old Jonas as he begins training for his new role in society. Jonas is his community’s new Receiver of Memory. He will receive and keep all of the world’s memories and knowledge, which are to be passed on to him by his predecessor, The Giver.

Prior to his training, Jonas’s Community was Utopian. Fear, chaos, hardship, and differences were concepts that were nebulous, if not downright nonexistent. Everything in the Community was designed for order, sameness, and peace. But as Jonas’s training progressed, he started seeing the other side of the coin. For the Community to attain “Utopia,” it needed to sacrifice wonderful and perhaps worthier values like individuality, freedom of choice, speech, and expression, and the capacity to feel emotions like love, happiness, anger, and grief. Through the world’s memories, Jonas remembered what could have been and what still could be—a world of freedom and possibility.

Lois Lowry’s The Giver is one of those books that I like to revisit at least once every decade. And every time I do, I’m amazed by the book’s continued relevance. Language-policing, mob mentality, the silencing of dissenting opinions, the oppression of what’s Other, tyranny—these are all things we continue to witness in today’s society. Honestly, we can all learn a little something from this book. So, if you haven’t read The Giver yet, please consider adding this to your reading list.

Grade: A+

Book 9: Make Good Art by Neil Gaiman (2012)

Favorite Quote: “Go and make interesting mistakes, make amazing mistakes, make glorious and fantastic mistakes. Break rules. Leave the world more interesting for your being here.”

As far as inspirational speeches go, this 19-minute commencement address by Neil Gaiman—delivered at Philadelphia’s University of the Arts in 2012—is one of the best you’ll find online. In it, Gaiman shares his thoughts on creativity, resilience, resourcefulness, and bravery. To make good art, one must be willing to put oneself out there. To make mistakes, to risk failure, to keep going even when the odds are stacked against you, especially when the odds are stacked against you. To keep believing in yourself and to keep soldiering on. All solid and effective advice.

Make Good Art is a heartwarming and rousing speech. It’s a pleasure to watch and listen to—and it makes for a quick but impactful read. This is the book for struggling and blocked artists and writers who need the occasional reminder that they have what it takes to make good art.

Rating: A-

Book 10: How to Be Parisian Wherever You Are: Love, Style, and Bad Habits by Caroline de Maigret, Sophie Mas, Audrey Diwan, Anne Berest

Favorite Quote: “Enjoy the face you have today. It’s the one you’ll wish you have ten years from now.”

Have I mentioned that I’m studying French? C’est plus difficile que je le pensais. I’m progressing a lot slower than I thought I would, but any progress is good progress, right? As part of my learning experience, I decided to read more French culture books. This year, How to Be Parisian Wherever You Are was my toe in the water.

Now, let me tell you, this was a fun ride. I was expecting something a little more serious and instructional, but what I got was far better. How to Be Parisian is a book that doesn’t take itself too seriously. It’s snobbish, pretentious, sassy, amusing, witty, sarcastic, and funny at points. It plays to and pokes fun at the stereotypes we have of Parisian women. It also has a number of great recipes that I can’t wait to try. It’s a good, fun book for when you need a chuckle.

Grade: B+