While reading up on Richard Feynman, I stumbled upon a fascinating article called The Feynman Technique: The Best Way to Learn Anything. This Farnam Street (FS) piece breaks down the Nobel Prize-winning physicist’s recommended method of learning. The basic premise is that if you want to learn something, pretend that you’re teaching it to a sixth-grader.

Now, due to a very real shortage of sixth-graders in our household, I’m modifying my application of the Feynman Technique. I’m substituting the teaching part with writing, specifically writing articles about Western Philosophy.

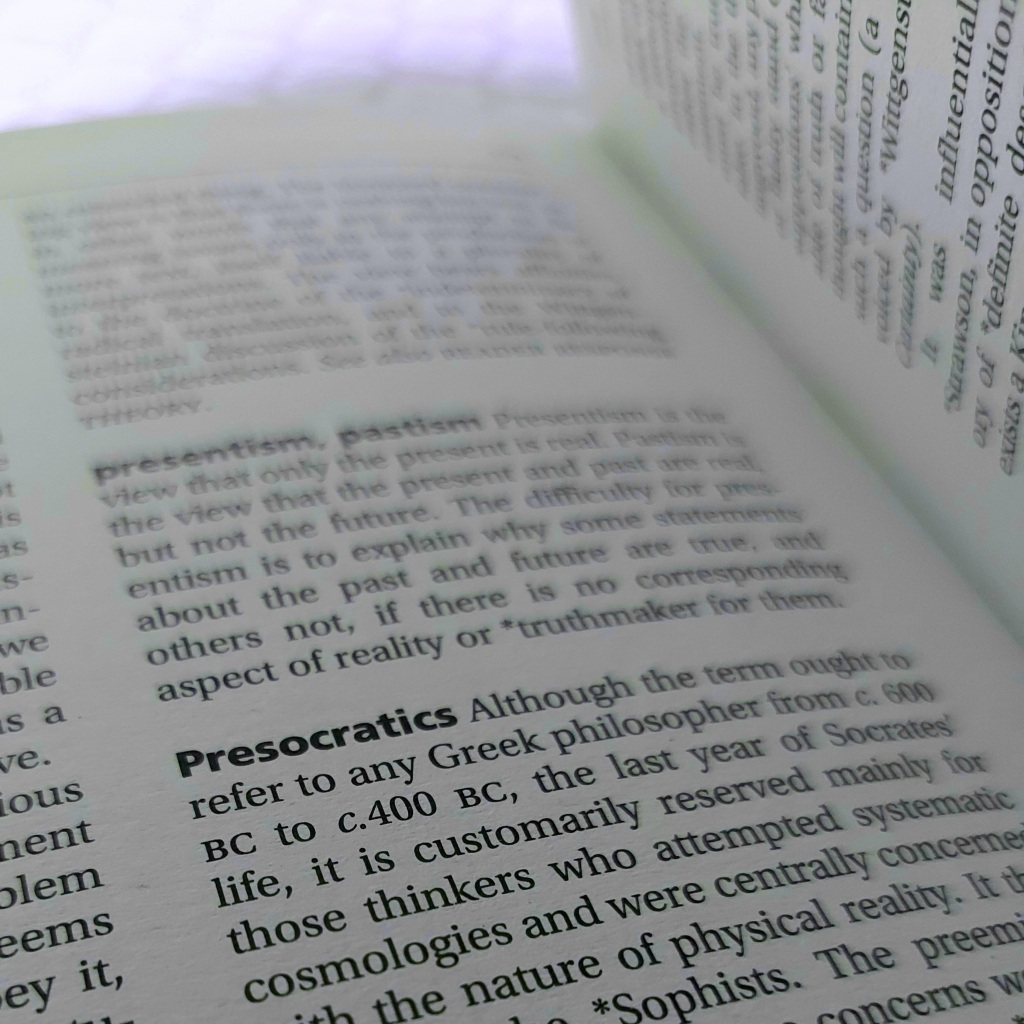

This is my attempt at a sixth-grade-worthy Presocratic Cheat Sheet.

Who were the Presocratics (Pre-Socratics)?

The Presocratics were a group of ancient Greek philosophers who flourished around the 6th and 5th century BCE. These ancient thinkers were often credited for kickstarting philosophy in the West and for being some of history’s first scientists. Using their commendable observation skills, an array of ancient math techniques, and the power of inference and deduction, the Presocratics sought to find rational answers to some of mankind’s hardest questions. We’re talking—Why are we here? Where does life come from? What is the Universe made of? How did the Universe begin? How was the world formed? Really thought-provoking questions.

With the advancement of science and technology, we can now say definitively that these philosophers did get a lot of things wrong. But they also got some things right—chief of which is asking the right questions. By asking the difficult questions and going for it, the Presocratics succeeded in changing the way man thinks, forever.

Presocratic philosophers have contributed greatly to science, math, and philosophy. One can even say that they have ushered in the birth of cosmology, logic, and metaphysics. Thanks in part to these early theorists, mankind has broken the tradition of blind belief, turning instead to critical thinking.

Socrates and the Presocratics

Now, with the way the word is structured, Pre-Socratic, it’s easy to assume that these thinkers all came before Socrates. But that assumption is only partially true. While a great number of Presocratic philosophers did precede the Athenian Gadfly, a few of them were his contemporaries.

See, contrary to its confusing prefix, Presocratic isn’t a chronological term. It’s more of an umbrella term or identifier used to describe a group of ancient Greek thinkers that were NOT influenced by Socrates’s teachings. In the end, it all boils down to a difference in topic. Bear in mind that:

Socratic teachings focus on ethics, political philosophy, moral philosophy, epistemology, teleology, and eudaimonia (the life worth living).

While Presocratic philosophy keeps the spotlight on nature, reason, existence, reality, and the universe. Sure, some of these early thinkers did touch on ethics, politics, and religion, but for the most part, their studies had more of a scientific bent. Dissatisfied with the ancient creation techniques, the Presocratics sought to find alternative, logical explanations for the universe’s, the world’s, and man’s existence.

The Different Presocratic Schools

There were several important schools and major players in the Presocratic scene. The following list is just going to be a quick run-through—a cheat sheet of sorts. I do plan on writing longer articles for each school or philosopher, but until then, we’ll go with key points.

THE MILESIAN SCHOOL (6th Century BCE)

The Milesian School gets its name from the ancient town of Miletus, a Greek colony situated on the western coast of Anatolia (a.k.a., modern-day Turkey). Its philosophers were preoccupied with finding the “material cause” or “basic material” of the universe—a substance which they referred to as the primary principle, the quintessential substance, or archê.

The school produced three key Presocratic thinkers: Thales of Miletus, Anaximander, and Anaximenes.

Thales of Miletus (c. 625-545/624-548 BCE)

“Water is the first principle of everything.”

Thales of Miletus is one of the most impressive philosophers on our list. He’s a member of the Seven Wise Men of Greece and is often regarded as the founding father of Western Philosophy—though some insist that this is a title he ought to share with Pythagoras of Samos.

Primary Principle: Water

Thales posited that all things originated from water. Depending on who you’re reading, he may have come to this conclusion based on his observations of how water can shift from gaseous to liquid to solid and back again via condensation, evaporation/vaporization, freezing, and melting.

Believed that the Earth is… a flat disk that rests on water.

Is Credited With… Measuring the height of the pyramids through the shadows they casted. He used his own shadow to find the right time to take the pyramids’ measurements.

Had pretty good estimates of the size of the moon and the sun.

Could determine the distance of ships from the shore.

Anaximander of Miletus (c. 610-546 BCE)

“The Earth is cylindrical, three times as wide as it is deep, and only the upper part is inhabited.”

Anaximander of Miletus is thought to have been Thales’s student and successor. He’s also arguably the first philosopher to have kept writings of his work.

Primary Principle: Apeiron

Like Thales, Anaximander thought that everything in existence originated from one substance. But unlike his master, Anaximander thought that this substance wasn’t something readily visible or tangible like water, earth, or fire. He thought it was a boundless, unlimited, interminable, and undefined stuff, which he called Apeiron. This substancethen produced opposites like hot and cold, dry and wet, which then brought on the creation of the world and all things in it.

Believed that the Earth is…cylindrical in shape.

Is Credited With… Making the first star chart and the first map of the world.

Creating the earliest Greek sundial.

Anaximenes of Miletus (c. 586-526 BCE/fl. 546-526 BCE)

“Just as our soul, being air, constrains us, so breath and air envelops the whole kosmos.”

There’s still some debate as to whether Anaximenes was a student or a friend of Anaximander’s, but what isn’t up for debate is how Anaximenes also subscribed to the idea of a quintessential or primary substance.

Primary Principle: Air

Anaximenes believed that air was the primary substance that made up and brought about the creation of the world. Like Thales, Anaximenes got this idea by observing his surroundings. He thought that air could transform itself into a myriad of other things like clouds, fire, water, wind, and even earth.

Believed that the Earth… was flat, like its surrounding heavenly bodies. He also asserted that the Earth breathed—which, if you think about it, is only partially wrong.

PYTHAGORAS of SAMOS (c.570-495 BCE) | PYTHAGOREAN SCHOOL

“All things are numbers.”

Now here’s a Presocratic school that’s named after its founder. With his invaluable contributions to math (specifically geometry) and philosophy, Pythagoras of Samos might just be one of the most important men in history. And yes, this is the same Pythagoras of the Pythagorean Theorem fame.

On Math and God. Pythagoras of Samos was a curious fellow. A true mathematician at heart, he asserted that mathematics is the key to learning more about the order and structure of the world and the universe. To Pythagoras, mathematics is everything—and the fact that we can explain much of the world through numbers shows that God is likely a geometer.

On Mysticism. Beyond being a school of mathematics, the Pythagorean School was also an ascetic religious brotherhood with exact rules and rituals. These practices ran the gamut of practical to borderline illogical. We’re talking selective vegetarianism, exclusively wearing white clothes, putting on the right shoe first, and the avoidance of beans at all cost.

Is credited with… inventing the word philosopher, from the word philosophos, which means ‘lover of wisdom.’

Discovering harmonic progression and harmonic mean. (The relationship between numerical ratios and musical intervals.)

XENOPHANES of COLOPHON (570-475/470 BCE)

“All things are from earth and in earth all things end.”

Xenophanes of Colophon wore a multitude of hats. He was a poet, a philosopher, a staunch critic of polytheism, and a theologian. He had a long life which he spent continually learning, traveling, and writing. Xenophanes often wrote about cosmology and his criticisms of mythology and religion.

On Cosmology. Xenophanes believed that there was a natural link between earth and water, and that water once covered the earth. This was a theory he posited after discovering fossils of sea creatures inland. He also believed that we experienced a new sun every day. Now, whether we’re talking solar regeneration or the actual replacement of the sun, I’m not quite sure. But either way, it’s not as solid as his theory on earth and water.

On Religion. Xenophanes was very much against polytheism and the idea that the gods were anthropomorphic. He criticized mythology and asserted his belief that there was only one God (monotheism) who could control everything with His thoughts.

Is credited with… the observation of fossil records.

EPHESIAN SCHOOL

The Ephesian School of philosophy was established during the 5th Century BCE and was based on the teachings of one philosopher—Heraclitus of Ephesus.

Heraclitus of Ephesus (535-475 BCE)

“You cannot step into the same river; for fresh waters are ever flowing in upon you.”

Most of us have come across the saying, “You can’t step in the same river twice.” The expression is often used as an illustration of how everything changes with the passing of time. Well, now it’s time to get to know the Greek philosopher who said it first—Heraclitus of Ephesus. Heraclitus is considered the most famous and the last of the Ionian Philosophers.

On Religion and Cosmology. Many historians think that Heraclitus may have been inspired by the philosophy of Xenophanes of Colophon. They definitely share certain beliefs. Both were very critical of religious sacrifice and the religion of their times. The two philosophers also suggested that the sun was new every day. This was consistent with Xenophanes’s belief in the Cosmic Principle of Reparation or the idea of the Universe as flux—a.k.a. the reason you can’t step in the same river twice.

Primary Principle: Fire

Heraclitus also had a theory on the primary substance of the universe. He believed that the world was ever-living fire. That the soul was made of fire and that fire had the power to change into any other element.

ELEATIC SCHOOL

The Eleatic School of philosophy was established in the 5th century BCE in the ancient city of Colophon in Ionia (present-day Turkey). Its founder, Parmenides of Elea, is believed to have been one of the students of Xenophanes of Colophon.

Parmenides of Elea (510-440 BCE)

“Ex nihilo nihil fit.” (Out of nothing, nothing is produced.)

On Reality and Metaphysics. If Heraclitus was all about movement and flux, Parmenides of Elea was the Ephesian thinker’s opposite. To Parmenides, everything is permanent and static. Nothing is ever in motion. The past, the present, and the future are one and the same.

He also believed that the only thing that is true is what is or what exists. And that to arrive at that truth, to understand and see reality for what it truly is, one has to use pure logic and reason. There’s no room for the subjective data provided by one’s senses because reality has nothing to do with what we experience.

Is Credited With… creating the founding charter for logic-based Metaphysics and Ontology.

Zeno of Elea (490-430 BCE)

“There is no motion, for whatever moves must reach the middle of its course before it reaches the end.”

On Motion. Like his predecessorParmenides, Zeno of Elea believed that nothing is in motion. Since he was a master at creating clever paradoxes, he used these arguments to illustrate the impossibility of movement. His most popular paradox may have been the Achilles and the Tortoise Paradox.

The paradox presented a race between Achilles and a tortoise—hardly seems fair, I know. But then, Zeno decides to try to level the playing field. Why not give the slow-moving tortoise a bit of a head start? Now, common sense tells us that despite the head start, Achilles should be able to catch up to the tortoise after a sprint. However, Zeno disagrees. According to the philosopher, there is bound to be a gap that never ends. Every time Achilles reaches the point where the tortoise was a moment ago, the tortoise would have since moved on.

Melissus of Samos (440 BCE)

“What was ever, and ever shall be. For, it came into being, necessarily, before its generation, there was nothing; so, if there was nothing, nothing at all would come from nothing.” QUOTE

On Reality and Metaphysics. If the idea of nothing arising out of nothing sounds familiar, that’s because Melissus of Samos expounds on the ideas of his master, Parmenides. Like Parmenides, Melissus believed in the unchangeable nature of the Universe. He saw the universe, and actually everything in existence, to be fixed, homogenous, and indivisible.

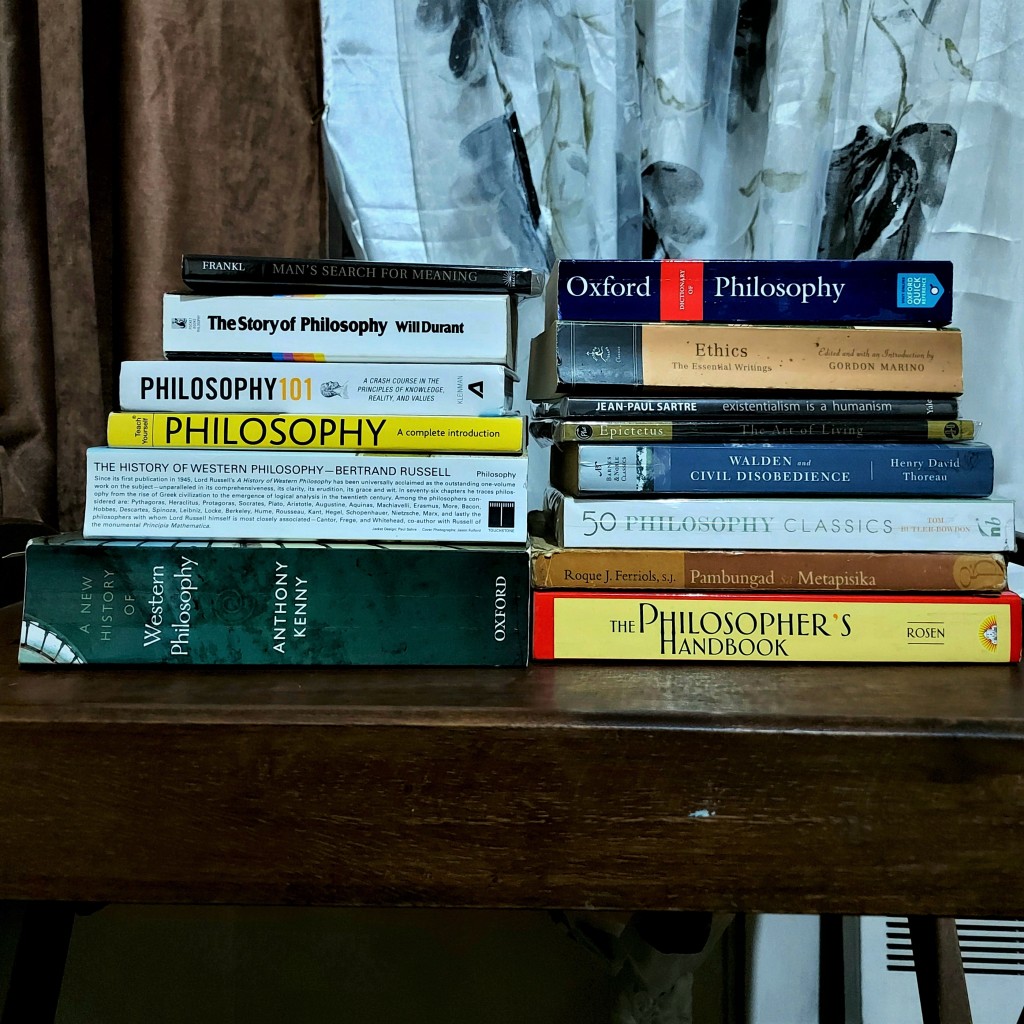

To the Presocratic philosopher, when a thing is x, it always will be x, and never not x.* Now, I know that sounds tricky, but author Paul Kleinman helps break this idea down in his book Philosophy 101. In Philosophy 101, Kleinman gives us the example of cold water. Imagine a glass of cold water—maybe straight from the fridge or filled with ice cubes. There’s no doubting the coldness of this cold water.

If we were to follow Melissus’s logic, that cold water will remain cold forever. But all of us know from experience that this simply isn’t true. A glass of cold water left on the counter for a day or two is bound to come down to room temperature. If it’s left in a hot car, the water may even become warm over time. And if you wait long enough, it will evaporate leaving no trace of water at all. So much for permanence, right? But that’s exactly Melissus’s point. Beyond absolute truth—or Parmenidean truth—nothing ever really is, it just seems.

On Pain and Vacuum. Melissus didn’t believe in pain and the vacuum. As per Melissus, pain isn’t real because the experience of pain implies imperfection in Being. As for the vacuum, its nothingness implies the absence of existence, which goes against the idea of the permanence of Being.

EMPEDOCLES (c. 494-434 BCE)

“Hear first the four roots of all things: shining Zeus, life-bringing Hera, Aidoneus, and Nestis, who wets with tears the mortal wellspring.”

Now, here was a philosopher who was able to bring together multiple philosophies and make them his own. Empedocles fuses the philosophies of the Ionians to explain the origins of the universe. Because he borrows concepts from different philosophers, many have alleged that Empedocles may have been a student of Pythagoras, Parmenides, or even Xenophanes. Aside from being a famous philosopher and an avid student to the earlier masters, Empedocles was also a democrat, a counsellor, and a physician.

On the Four Classic Elements as the Roots of the Universe. Empedocles is credited for bringing together the four classic elements—Water (Thales), Fire (Heraclitus), Air (Anaximenes), and Earth (Xenophanes)—and presenting them as the base ingredients of the Universe. What sets Empedocles apart from his predecessors, however, is that he presents these elements as equal contributors/ingredients.

Now, if the four elements are ingredients, implying passivity from their end, they’re going to need a catalyst or an agent of change to bring them together and to get them to interact. According to Empedocles, these agents are Love and Strife. Love unites the elements and Strife pulls them apart. This “coming together and breaking apart” action is what leads to the creation of more complex beings.

ANAXAGORAS (c. 500-428 BCE)

“All things were together, infinite both in number and in smallness; for the small too was infinite.”

As far as philosopher nicknames go, Anaxagoras has one of the best ones. He was called “The Mind,” a nickname he received due to his study of the Nous (Cosmic Mind) and the role it plays in the creation of the universe.

On the Concept of Nous/The Cosmic Mind. A student of Anaximenes, Anaxagoras, like his master, had a special interest in the way the Universe worked. He believed that the Nous/Mind was divine and unlimited and that it was separate from the body. According to Anaxagoras, the Cosmic Mind set creation into motion and still continues the development of the Universe.

Is Credited With… being the intellectual ancestor of the Big Bang Theory. One of Anaxagoras’s cosmology theories is that the Universe began as a primordial pebble—compact and dense with possibility. The pebble started spinning and threw off air and ether to create the moon and the sun. Anaxagoras also posited that the Universe was ever-expanding, creating multiple worlds like ours.

THE ATOMIST SCHOOL

“Nothing exists except atoms and empty space; everything else is opinion.” – Democritus

The Atomist School was started by Leucippus of Miletus (fl. 5th century BCE) and was continued by his student Democritus of Abdera (c. 460-370 BCE). Because the two philosophers are often mentioned together, it’s difficult to distinguish each one’s contribution to the theories of Atomism. So, to keep things simple, in this section we’re going to be discussing the Atomist ideas in general.

On Atoms and the Void. The Atomistsbelieved that the physical universe was made up of the Void (the great nothingness) and these miniscule and indivisible bodies called Atoms, (atom being the Greek word for indivisible). So, yes, I think we’re pretty much talking about the same atoms that we studied in science class.

Now, according to the Atomists, atoms are so tiny that it’s impossible to see them with the naked eye. They are also infinite in number and exist in the void. While the void may be vast, the atoms are in constant motion, which means that they frequently collide. Upon impact, the atoms merge to form anything and everything that’s visible and in existence.

Other Philosophy Posts:

Philosophy 101: The Six Branches of Philosophy

Memento Homo: Finding Meaning in Your Mortality

Sources

Kenny, A. (2012). A New History of Western Philosophy (Reprint ed.). Oxford University Press

Kleinman, P. (2013). Philosophy 101: From Plato and Socrates to Ethics and Metaphysics, an Essential Primer on the History of Thought (Adams 101) (Illustrated ed.). Adams Media

Russell, B. (1967). A History of Western Philosophy) Simon & Schuster/Touchstone

Presocratics Entry at Stanford.edu

Hermann Alexander Diehls – Wikipedia

Presocratics – Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy